Using a solid electrolyte as a substitute of a liquid one inside a battery could enable rechargeable lithium metal batteries which can be safer, store rather more energy, and recharge far faster than today’s lithium-ion batteries. This concept has attracted scientists and engineers for many years. Nevertheless, progress has been limited by a critical weakness. Solid electrolytes produced from crystalline materials are inclined to develop microscopic cracks. Over time, these cracks grow during repeated charging and eventually cause the battery to fail.

Researchers at Stanford, constructing on work they published three years ago that exposed how tiny cracks, dents, and surface defects form and spread, have now identified a possible fix. They found that heat-treating an especially thin layer of silver on the surface of a solid electrolyte can largely prevent this damage.

As reported in Nature Materials on January 16, the silver-treated surface became five times more immune to cracking brought on by mechanical pressure. The coating also reduced the danger that lithium would push its way into existing surface flaws. The sort of intrusion is particularly harmful during fast charging, when very small cracks can widen into deeper channels that permanently degrade the battery.

Why Cracks Are So Hard to Eliminate

“The solid electrolytes that we and others are working on is a type of ceramic that permits the lithium-ions to shuttle backwards and forwards easily, however it’s brittle,” said Wendy Gu, associate professor of mechanical engineering and a senior creator of the study. “On an incredibly small scale, it isn’t unlike ceramic plates or bowls you’ve at home which have tiny cracks on their surfaces.”

Gu noted that eliminating every defect during manufacturing is unrealistic. “An actual-world solid-state battery is fabricated from layers of stacked cathode-electrolyte-anode sheets. Manufacturing these without even the tiniest imperfections could be nearly not possible and really expensive,” she said. “We decided a protective surface could also be more realistic, and just slightly little bit of silver seems to do a reasonably good job.”

Silver-Lithium Switch

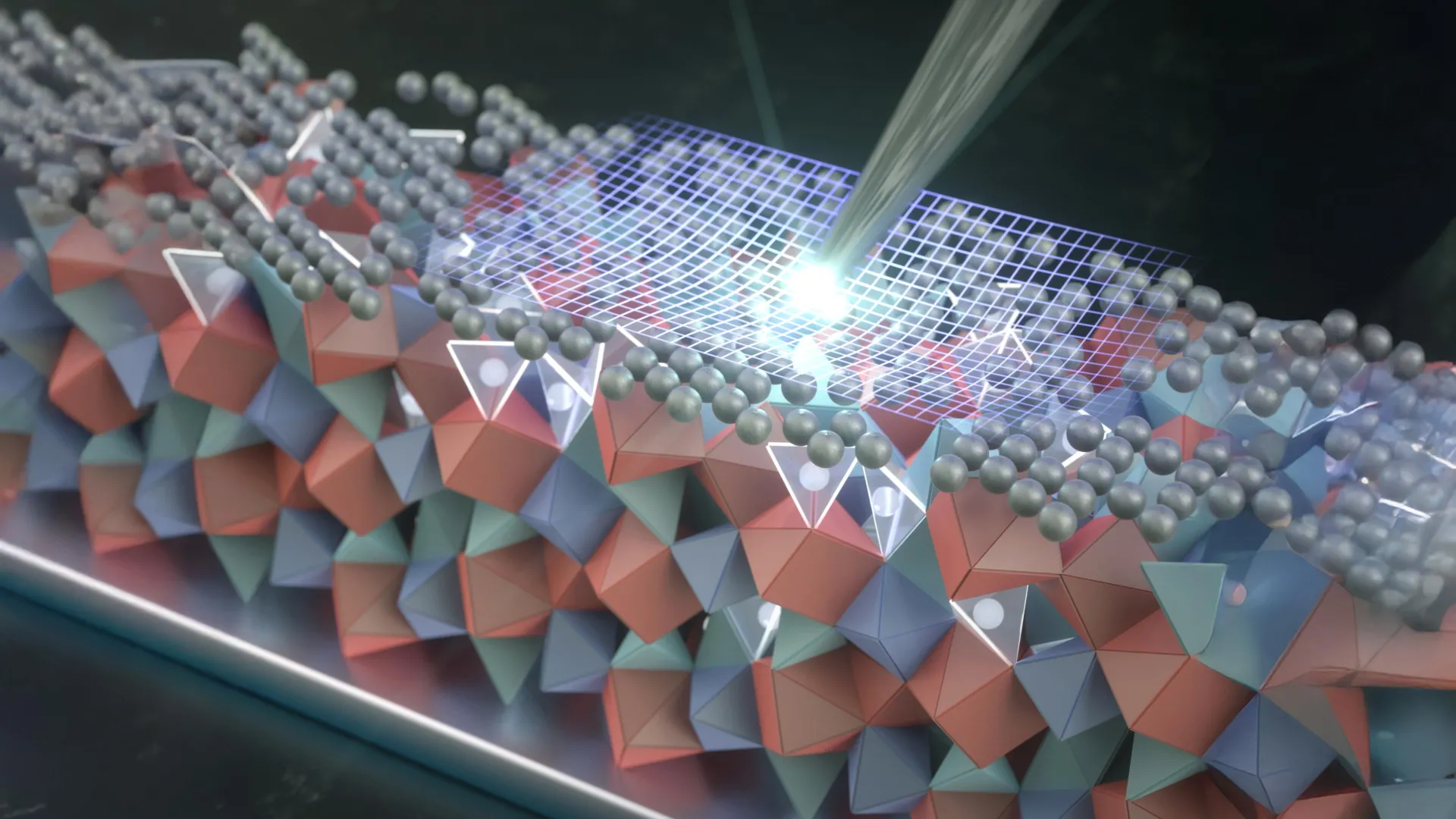

Earlier studies by other research teams examined metallic silver coatings applied to the identical solid electrolyte material utilized in the brand new study. That material is generally known as “LLZO” for its combination of lithium, lanthanum, zirconium, and oxygen. While those earlier efforts focused on metallic silver, the Stanford team took a unique approach through the use of a dissolved type of silver that has lost an electron (Ag+).

This positively charged silver behaves very in another way from solid metallic silver. In line with the researchers, the Ag+ ions are directly answerable for strengthening the ceramic and reducing its tendency to crack.

How the Silver Treatment Works

The team applied a silver layer just 3 nanometers thick to the surface of LLZO samples after which heated them to 300 degrees Celsius (572° Fahrenheit). Because the samples heated, silver atoms moved into the surface of the electrolyte, replacing smaller lithium atoms throughout the porous crystal structure. This process prolonged about 20 to 50 nanometers below the surface.

Importantly, the silver remained in its positively charged ionic form fairly than turning into metallic silver. The researchers consider that is critical to stopping cracks. In areas where tiny imperfections exist already, the silver ions also help block lithium from entering and forming damaging internal structures.

“Our study shows that nanoscale silver doping can fundamentally alter how cracks initiate and propagate on the electrolyte surface, producing durable, failure-resistant solid electrolytes for next-generation energy storage technologies,” said Xin Xu, who led the research as a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford and is now an assistant professor of engineering at Arizona State University.

“This method could also be prolonged to a broad class of ceramics, It demonstrates ultrathin surface coatings could make the electrolyte less brittle and more stable under extreme electrochemical and mechanical conditions, like fast charging and pressure,” said Xu, who at Stanford worked within the laboratory of Prof. William Chueh, a senior creator of the study and director of the Precourt Institute for Energy, which is a component of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

To measure how much stronger the treated material had change into, the researchers used a specialized probe inside a scanning electron microscope to check how much force was needed to fracture the electrolyte surface. The silver-treated material required almost five times more pressure to crack than untreated samples.

What Comes Next for Solid-State Batteries

Up to now, the experiments focused on small, localized areas fairly than full battery cells. It remains to be unclear whether this silver-based approach could be scaled to larger batteries, integrated with other components, and maintain its performance over 1000’s of charging cycles.

The team is now working with complete lithium metal solid-state battery cells and exploring how applying mechanical pressure from different angles might extend battery lifespan. Also they are studying additional varieties of solid electrolytes, including sulfur-based materials that would offer higher chemical stability when paired with lithium.

The researchers also see potential applications beyond lithium. Sodium-based batteries may benefit from similar strategies and will help reduce supply-chain pressures tied to lithium demand.

Silver is probably not the one viable option. The researchers said other metals could work, so long as their ions are larger than the lithium ions they replace within the electrolyte structure. Copper showed some success in early tests, even though it was less effective than silver.

The opposite senior authors of the study with Gu and Chueh is Yue Qi, engineering professor at Brown University. Stanford co-lead authors with Xu are Teng Cui, now an assistant professor on the University of Waterloo; Geoff McConohy, now a research engineer at Orca Sciences; and current PhD student Samuel S. Lee. Brown University alumnus Harsh Jagad, now chief technology officer at Metal Light, Inc., can also be a co-lead creator of the study.