Within the seventeenth century, astronomers Christiaan Huygens and Giovanni Cassini pointed a number of the earliest telescopes at Saturn and made a surprising discovery. The brilliant structures across the planet weren’t solid extensions of the world itself, but separate rings formed from many thin, nested arcs.

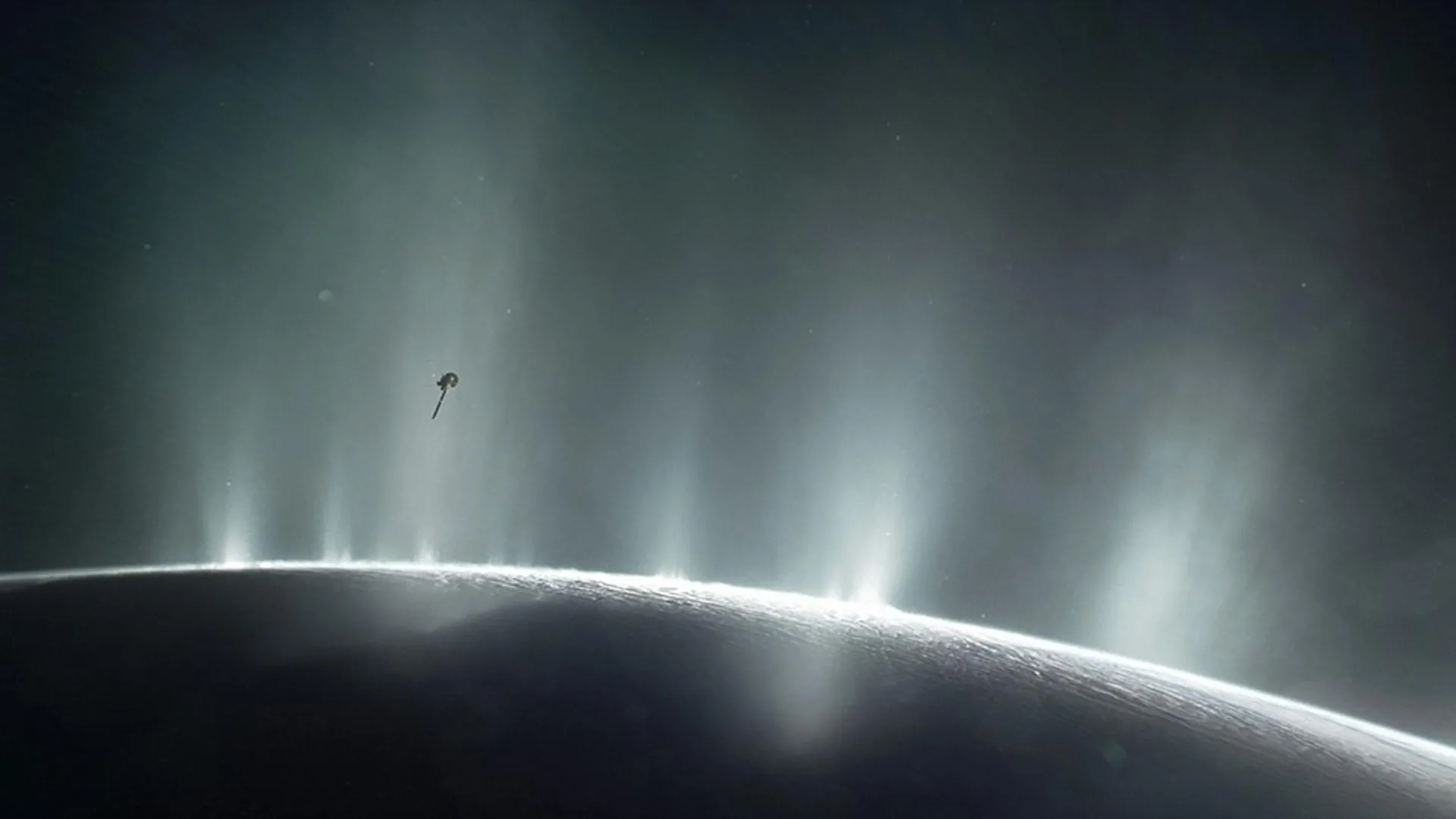

Centuries later, NASA’s Cassini-Huygens (Cassini) mission carried that exploration into the space age. Starting in 2005, the spacecraft returned a flood of detailed images that reshaped scientists’ view of Saturn and its moons. One of the dramatic findings got here from Enceladus, a small icy moon where towering geysers shot material into space, making a faint sub-ring around Saturn fabricated from the ejected debris.

Recent computer simulations run on the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC), using data collected by Cassini, now provide refined estimates of how much ice Enceladus is losing to space. The updated numbers are necessary for understanding the moon’s internal activity and for planning future robotic missions that will explore its buried ocean, which could potentially support life.

“The mass flow rates from Enceladus are between 20 to 40 percent lower than what you discover within the scientific literature,” said Arnaud Mahieux, a senior researcher on the Royal Belgian Institute for Space Aeronomy and an affiliate of the UT Austin Department of Aerospace Engineering & Engineering Mechanics.

Supercomputers and DSMC Models Reveal Plume Physics

Mahieux is the corresponding creator of a computational study of Enceladus published August 2025 within the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. On this work, he and his collaborators used Direct Simulation Monte Carlo (DSMC) models to raised describe how enormous plumes of water vapor and icy grains behave after erupting from cracks and vents on the surface of Enceladus.

The project builds on earlier research led by Mahieux and published in 2019. That previous study was the primary to make use of DSMC techniques to pin down the starting conditions for the plumes, including the dimensions of the vents, the ratio of water vapor to solid ice grains, the temperature of the fabric, and the speed at which it escapes into space.

“DSMC simulations are very expensive,” Mahieux said. “We used TACC supercomputers back in 2015 to acquire the parameterizations to cut back computation time from 48 hours then to simply just a few milliseconds now.”

Using these mathematical parameterizations, the team calculated key properties of Enceladus’s cryovolcanic plumes, comparable to how dense they’re and how briskly the gas and particles move. They based their calculations on Cassini measurements collected while the spacecraft flew directly through the jets.

“The important finding of our recent study is that for 100 cryovolcanic sources, we could constrain the mass flow rates and other parameters that weren’t derived before, comparable to the temperature at which the fabric was exiting. It is a big step forward in understanding what’s happening on Enceladus,” Mahieux said.

A Tiny Moon With Powerful Cryovolcanic Jets

Enceladus is a comparatively small moon, only about 313 miles wide, and its weak gravity just isn’t strong enough to maintain the erupting jets from escaping into space. The brand new DSMC models are designed to represent this low-gravity environment accurately. Earlier models didn’t capture the physics and gas dynamics in as much detail as the present DSMC approach.

Mahieux compares the phenomenon to a volcanic eruption. What Enceladus does is akin to a volcano hurling lava into space — except the ejecta are plumes of water vapor and ice.

The simulations track how gas within the plumes behaves on very small scales, where individual particles move, collide, and transfer energy in a way much like marbles bouncing into each other. The models follow several tens of millions of molecules in time steps measured in microseconds. Due to the DSMC method, scientists can now simulate conditions at lower, more realistic pressures and permit for longer distances between collisions than previous models could handle.

The Planet Code and the Power of TACC Supercomputers

David Goldstein, a professor at UT Austin and co-author of the study, led the event in 2011 of the DSMC code often called Planet. TACC granted Goldstein computing time on its Lonestar6 and Stampede3 supercomputers through The University of Texas Research cyberinfrastructure portal, which provides resources to researchers across all 14 UT system institutions.

“TACC systems have an exquisite architecture that provide plenty of flexibility,” Mahieux said. “If we’re using the DSMC code on only a laptop, we could only simulate tiny domains. Because of TACC, we will simulate from the surface of Enceladus as much as 10 kilometers of altitude, where the plumes expand into space.”

Enceladus and the Family of Icy Ocean Worlds

Saturn orbits beyond what astronomers call the “snow line” within the solar system, together with other giant planets that host icy moons, including Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune.

“There’s an ocean of liquid water under these ‘big balls of ice,'” Mahieux said. “These are many other worlds, besides the Earth, which have a liquid ocean. The plumes at Enceladus open a window to the underground conditions.”

Since the plumes carry material from deep below the surface into space, they provide a rare natural sample of the hidden ocean, without the necessity to drill through miles of ice.

Future Missions and the Seek for Life

NASA and the European Space Agency are planning recent missions that will return to Enceladus with way more ambitious goals than easy flybys. Some proposals envision landing spacecraft on the surface and drilling through the crust to achieve the ocean beneath, to be able to search for chemical signs of life that could be preserved there.

Within the meantime, measuring what’s contained in the plumes and the way much material they carry gives scientists a robust indirect approach to study the subsurface environment. By analyzing the jets, researchers can infer conditions within the ocean without having to physically bore through the ice shell.

“Supercomputers can provide us answers to questions we couldn’t dream of asking even 10 or 15 years ago,” Mahieux said. “We are able to now get much closer to simulating what nature is doing.”