From restoring movement and speech in individuals with paralysis to fighting depression, brain implants have fundamentally modified lives.

But inserting implants, nevertheless small or nimble, requires dangerous open-brain surgery. Pain, healing time, and potential infections aside, the danger limits the technology to only a handful of individuals.

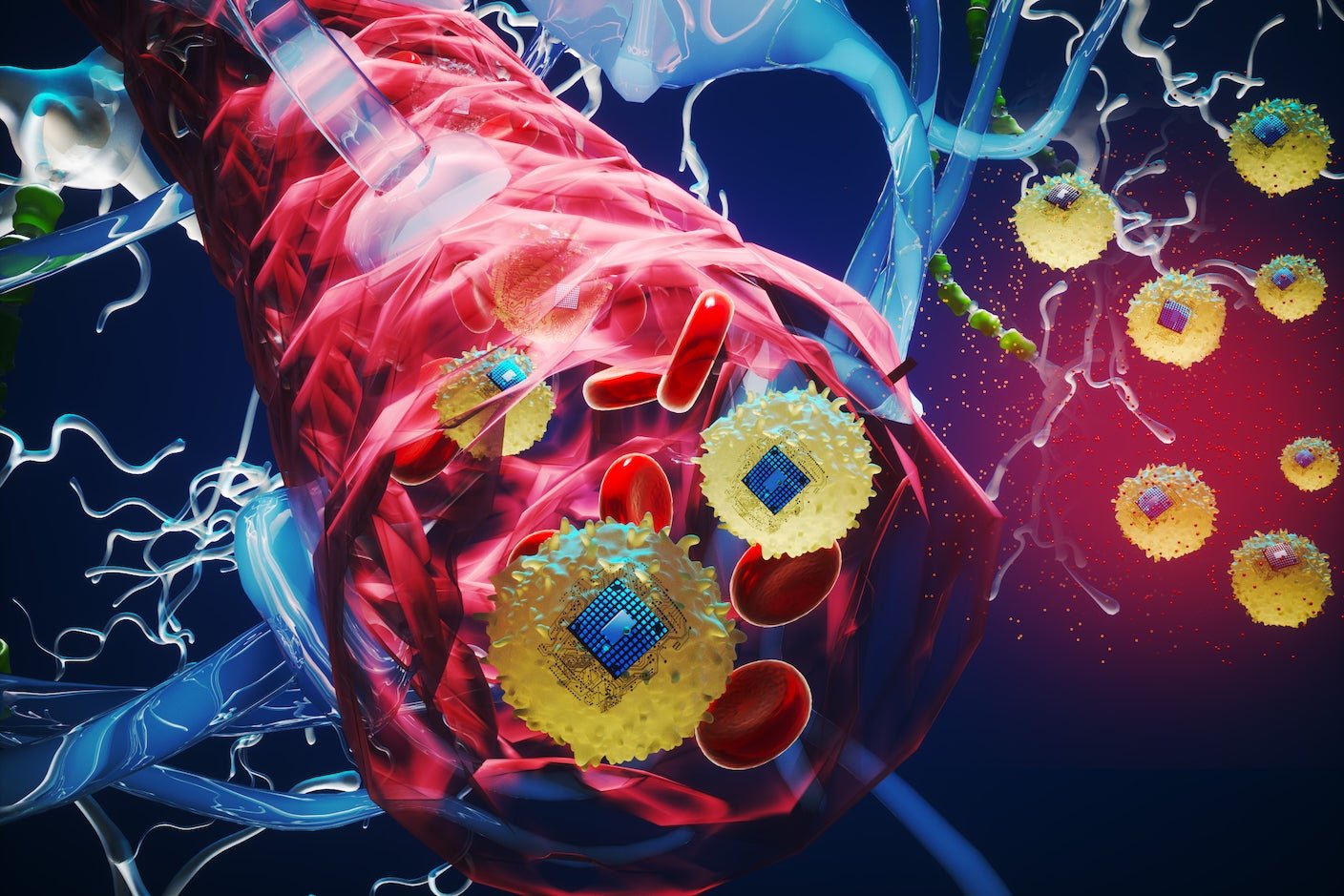

Now, scientists at MIT Media Lab and collaborators hope to bring brain implants to the masses. They’ve created a tiny electronic chip powered by near-infrared light that may generate small electrical zaps. After linking with a style of immune cell to form bio-electronic hybrid chips, a single injection into the veins of mice shuttled the devices into their brains—no surgery required.

It appears like science fiction, however the injected chips easily navigated the brain’s delicate and elaborate vessels to zero in on an inflamed site, where the microchip reliably delivered electrical pulses on demand. The chips happily cohabitated with surrounding neurons without changing the cells’ health or behavior.

“Our cell-electronics hybrid fuses the flexibility of electronics with the biological transport and biochemical sensing prowess of living cells,” said study creator Deblina Sarkar in a press release.

The strategy, which the researchers call circulatronics, could seriously change brain stimulation. Targeted electrical zaps have shown early promise for treatment of a wide range of brain diseases, resembling Alzheimer’s, depression, and brain tumors.

And since the devices could be engineered to dissolve after a certain quantity of time, they may potentially collect neural signals from healthy people, providing an unprecedented look into our brain’s inner workings.

A Long Road

Today’s brain implants are relatively bulky and struggle to achieve deep into the brain. Most use batteries, either directly contained in the device or in a battery pack affixed to the skull.

A really perfect implant can be self-powered, controllable, and sufficiently small to maneuver through the smallest nooks and crannies of the brain and its vessels. A previous device, concerning the size of a grain of rice, used magnetic energy for power and generated electrical zaps in rodents while they actively roamed around. But since the device was controlled by magnetic fields, the setup required large and expensive hardware. Magnetic particles also are inclined to move in straight lines. This makes them terrible at navigating our brains serpentine vessels.

Near-infrared light offers an alternative choice to magnetic control. The wavelength easily penetrates the skull and brain with minimal scattering, suggesting it could control devices deep within the brain. Earlier this month, a team engineered an infrared-powered implant smaller than a grain of salt that would record from or stimulate neurons in mice. Although the device still required minimal surgery to implant, it reliably captured brain signals for a 12 months, roughly half a mouse’s lifespan.

Infrared light has long been on Sarkar’s radar for an injectable brain implant. For six years, her team worked to unravel multiple difficult roadblocks, eventually landing on circulatronics.

Tag Team

The team first needed to make a chip so small it could easily flow through blood vessels without damaging them. The team turned to photovoltaic components that convert light into electricity, just like the best way solar panels work.

The chips are manufactured from organic semiconductors which can be biocompatible and versatile. This makes them suitable for navigation of our squishy bodies. Every one is sort of a tiny, light-powered battery sandwich, with a positive and negative metallic layer and an organic polymer inner filling.

Roughly 10 microns in diameter and smaller than a cell, these chips could be manufactured en masse with the identical technology used to make computer chips. In tests with molds simulating the brain, the chips reliably generated electrical currents.

Then there was the issue of getting the chips to their goal. The brain is protected by a wall of cells called the blood-brain barrier. The barrier is amazingly selective of what molecules, proteins, and other materials can enter. Electronics, regardless of how small, don’t make the cut. Some studies have tried to deliberately pry open the blood-brain barrier, but even a temporary opening invites pathogens and other dangerous molecules inside.

The team’s solution was a cellular Trojan horse. When the brain experiences inflammation, the blood-brain barrier admits immune cells called monocytes. These cells roam the bloodstream equipped with chemical beacons to seek out inflammatory sites. In theory, microchips could catch a ride on these cells through the blood-brain barrier without forcing it open.

To link monocytes to their tiny chip, the team used a Nobel Prize-winning technology called click chemistry. Consider it as Velcro. The researchers altered the surfaces of the monocytes in such a way that they formed Velcro-like “loops.” Then they added chemical “hooks” to the chips. When these components met, they clicked into place—but were still easily detachable—to form the ultimate implant.

“The living cells camouflage the electronics in order that they aren’t attacked by the body’s immune system, they usually can travel seamlessly through the bloodstream. This also enables them to squeeze through the intact blood-brain barrier without the necessity to invasively open it,” said Sarkar.

Roaming Biohybrid Bots

To check their hybrid implants, the team tagged them with glow-in-the-dark trackers and injected them into the veins of mice. The critters had been given a chemical that triggered inflammation at a particular site deep of their brains.

Inside 72 hours, the hybrid chips self-implanted into the inflamed area, whereas electronics lacking a cellular partner were barred from the brain. On average, around 14,000 hybrid implants latched onto the brain.

The devices worked as expected. After receiving pulses of near-infrared light for 20 minutes, neurons within the implanted region spiked with electrical activity at a magnitude just like spikes trigged by current brain implants. Neighboring neurons were undisturbed.

The hybrid implants didn’t appear to affect the brain’s activity. Animals with the implant roamed around as usual. They showed no sign of changes to mood, memory, or other cognitive functions, happily sipping water and maintaining body weight for six months. Despite circulating within the blood after injection, the hybrid implants had no observable impact on other organs.

Although this study focused on brain inflammation, the same strategy might be used to shuttle brain stimulation chips into stroke sites to help rehabilitation. The system is comparatively plug-and-play. Swapping monocytes for other cell types, resembling T cells or neural stem cells, could allow them to act like cellular taxis for a wide selection of other diseases.

The team hopes to kick off clinical trials of the technology inside three years through MIT spinoff company, Cahira Technologies.

“This can be a platform technology and will be employed to treat multiple brain diseases and mental illnesses,” said Sarkar. “Also, this technology shouldn’t be just confined to the brain but is also prolonged to other parts of the body in future.”