Neutrinos are amongst probably the most puzzling particles known to science and are sometimes called ‘ghost particles’ because they so rarely interact with matter. Trillions go through everybody every second without leaving any mark. These particles are created during nuclear reactions, including those contained in the Sun’s core. Their extremely weak interactions make them exceptionally difficult to check. Only a number of materials have ever been shown to answer solar neutrinos. Scientists have now added one other to that short list by observing neutrinos convert carbon atoms into nitrogen inside a large underground detector.

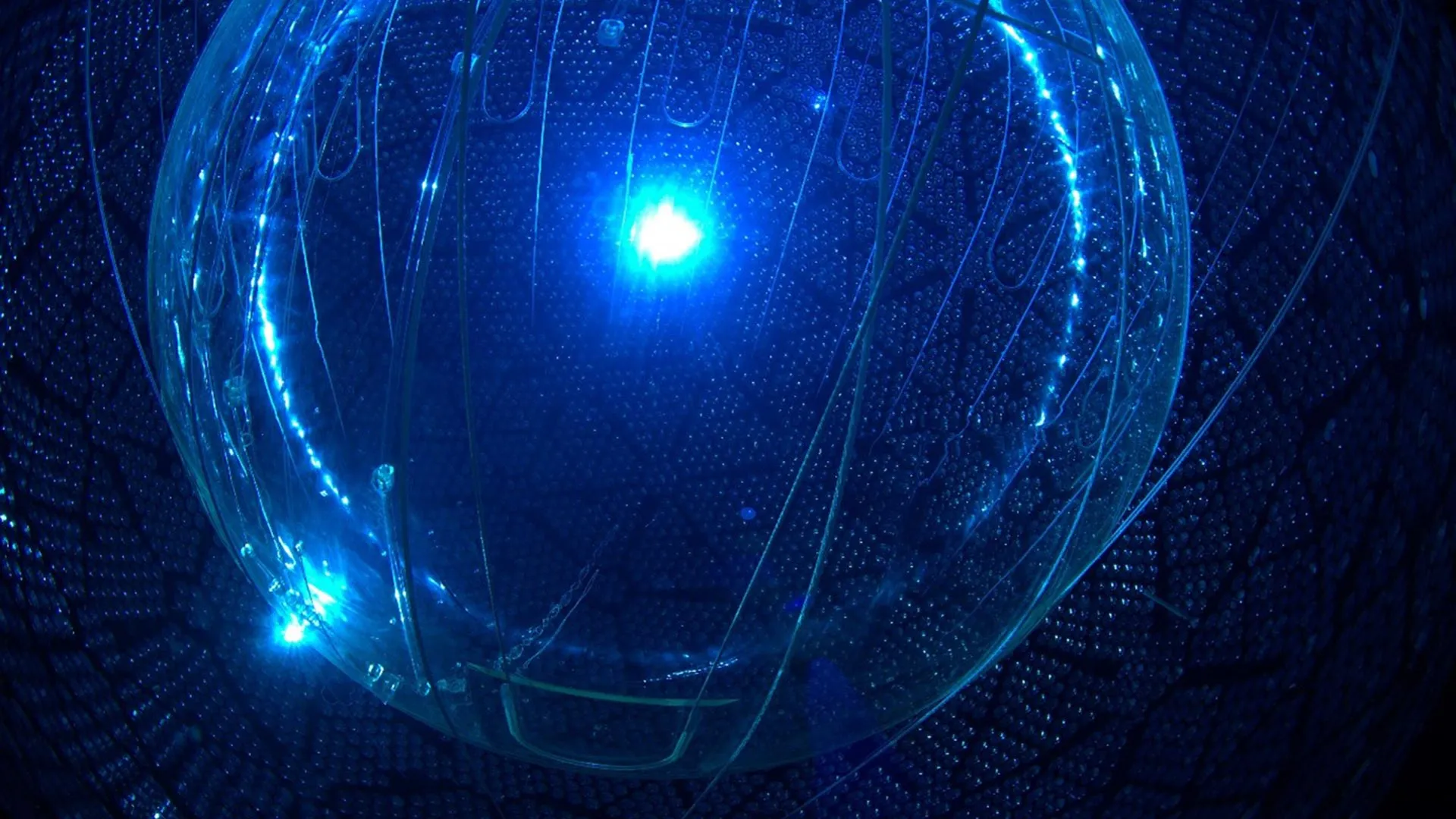

This achievement got here from a project led by Oxford researchers using the SNO+ detector, which sits two kilometers underground at SNOLAB in Sudbury, Canada. SNOLAB operates inside an energetic mine and provides the shielding needed to dam cosmic rays and background radiation that will otherwise overwhelm the fragile neutrino measurements.

Capturing a Rare Two-Part Flash From Carbon-13

The research team focused on detecting moments when a high-energy neutrino hits a carbon-13 nucleus and converts it into nitrogen-13, a radioactive type of nitrogen that decays roughly ten minutes later. To identify these events, they relied on a ‘delayed coincidence’ technique that searches for 2 related bursts of sunshine: the primary from the neutrino striking the carbon-13 nucleus and the second from the decay of nitrogen-13 several minutes afterward. This paired signal makes it possible to confidently distinguish true neutrino events from background noise.

Over a span of 231 days, from May 4, 2022, to June 29, 2023, the detector recorded 5.6 such events. This matches expectations, which predicted that 4.7 events would occur on account of solar neutrinos during this era.

A Recent Window Into How the Universe Works

Neutrinos behave in unusual ways and are key to understanding how stars operate, how nuclear fusion unfolds, and the way the universe evolves. The researchers say this latest measurement opens opportunities for future studies of other low-energy neutrino interactions.

Lead writer Gulliver Milton, a PhD student within the University of Oxford’s Department of Physics, said: “Capturing this interaction is a rare achievement. Despite the rarity of the carbon isotope, we were in a position to observe its interaction with neutrinos, which were born within the Sun’s core and traveled vast distances to succeed in our detector.”

Co-author Professor Steven Biller (Department of Physics, University of Oxford) added: “Solar neutrinos themselves have been an intriguing subject of study for a few years, and the measurements of those by our predecessor experiment, SNO, led to the 2015 Nobel Prize in physics. It’s remarkable that our understanding of neutrinos from the Sun has advanced a lot that we will now use them for the primary time as a ‘test beam’ to check different kinds of rare atomic reactions!”

Constructing on the SNO Legacy and Advancing Neutrino Research

SNO+ is a successor to the sooner SNO experiment, which demonstrated that neutrinos switch between three forms referred to as electron, muon, and tau neutrinos as they travel from the Sun to Earth. Based on SNOLAB staff scientist Dr. Christine Kraus, SNO’s original findings, led by Arthur B. McDonald, resolved the long-standing solar neutrino problem and contributed to the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physics. These results paved the best way for deeper investigations into how neutrinos behave and their significance within the universe.

“This discovery uses the natural abundance of carbon-13 inside the experiment’s liquid scintillator to measure a selected, rare interaction,” Kraus said. “To our knowledge, these results represent the bottom energy commentary of neutrino interactions on carbon-13 nuclei so far and provides the primary direct cross-section measurement for this specific nuclear response to the bottom state of the resulting nitrogen-13 nucleus.”