As data-center energy bills grow exponentially, technology corporations want to nuclear for reliable, carbon-free power. Meta has now made an unusually direct bet on a startup developing small modular reactor technology by agreeing to finance the fuel for its first reactors.

The nuclear industry’s flagging fortunes have rebounded lately as corporations like Google, Amazon, and Microsoft have signed long-term deals with providers and invested in startups developing next-generation reactors. US nuclear capability is forecast to rise 63 percent in the approaching many years thanks largely to data-center demand.

But Meta has gone a step further by prepaying for power from Oklo, a US startup constructing small modular reactors. Oklo will use the money to obtain nuclear fuel for a 1.2-gigawatt plant in Ohio that might come online as early as 2030.

The deal is an element of Meta’s broader nuclear investment strategy. Other agreements include a partnership with utility company, Vistra, to increase and expand three existing reactors and one with Bill Gates-backed TerraPower to develop advanced small modular reactors. Together, the projects could deliver as much as 6.6 gigawatts of nuclear power by 2035. And that’s on top of a deal last June with Constellation Energy to increase the lifetime of its Illinois power station for an extra 20 years.

“Our agreements with Vistra, TerraPower, Oklo, and Constellation make Meta some of the significant corporate purchasers of nuclear energy in American history,” Joel Kaplan, Meta’s chief global affairs officer, said in a press release.

While utilities commonly negotiate long-term fuel contracts, this appears to be the primary instance of a tech company purchasing the fuel that may generate the electricity it plans to purchase, based on Koroush Shirvan, a researcher at MIT. “I’m trying to consider some other customers who provide fuel aside from the US government,” Shirvan toldWired. “I am unable to consider any.”

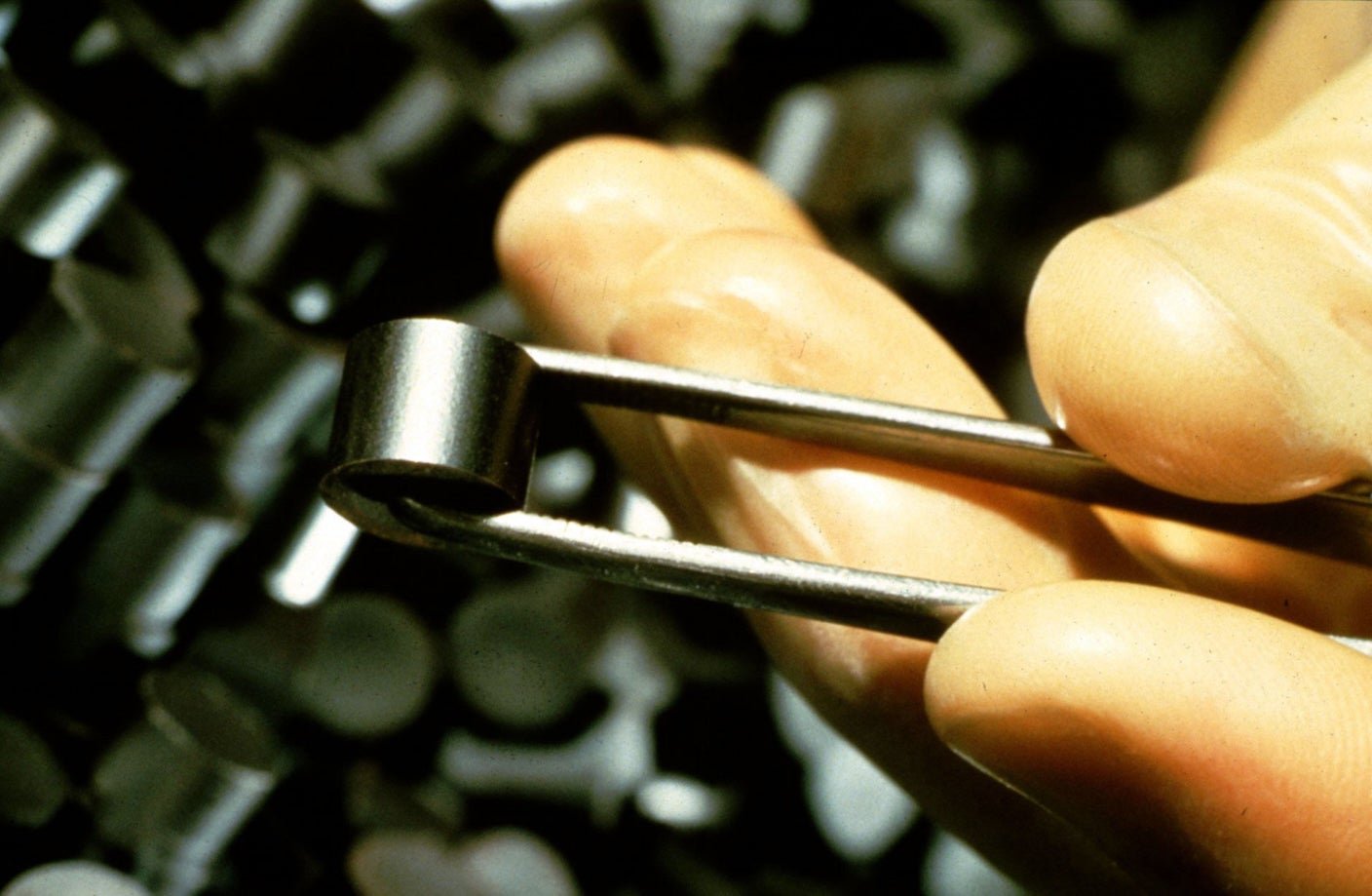

A part of the explanation for the bizarre deal is that securing fuel for advanced reactor designs like Oklo’s is just not easy. The corporate requires a special sort of fuel called high-assay low-enriched uranium, or HALEU, which is roughly 4 times more enriched than traditional reactor fuel.

This more concentrated fuel is critical for constructing smaller, more efficient nuclear reactors. American corporations are racing to grow the capability to develop this fuel domestically, but at present, the one business vendors are Russia and China. And with a federal ban on certain uranium imports from Russia, the worth of nuclear fuel has been rising rapidly.

Oklo will use the money from Meta to secure fuel for the primary phase of its Pike County power plant, which is able to supply the grid serving Meta’s data centers within the region. The ability is targeting a 2030 launch, though it won’t be producing the total 1.2 gigawatts until 2034.

It’s a somewhat dangerous bet for the tech giant. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission rejected Oklo’s licence application in 2022, and it has yet to resubmit. An anonymous former NRC official who handled the appliance recently told Bloomberg the corporate “might be the worst applicant the NRC has ever had.”

But Meta isn’t putting all its eggs in a single basket.

The take care of TerraPower will help fund development of two reactors able to generating as much as 690 megawatts by 2032, with rights for energy from as much as six additional units by 2035. “We’re getting paid to begin a project, which is admittedly different,” TerraPower CEO Chris Levesque told The Wall Street Journal. “That is an order for real work to start a megaproject.”

And the agreement with Vistra is more conventional. Meta is committing to buy greater than 2.1 gigawatts over 20 years from the present capability of the utility’s Perry and Davis-Besse plants in Ohio. It would purchase one other 433 megawatts from expanding capability at each plants in addition to the Beaver Valley plant in Pennsylvania. All three plants had been expected to shut just a couple of years ago, but Vistra is now planning to use for licence extensions.

The three deals represent a daring bet on nuclear power’s potential to fulfill AI’s future energy demands. The large query is whether or not AI will still depend on the identical sort of power-hungry models now we have today by the point these plants come online next decade. Regardless, the present AI boom helps power a nuclear renaissance that we may all profit from within the years to return.