A brand new study from geophysicists at Washington State University sheds light on how nutrients could travel from the surface of Europa into the moon’s hidden ocean. Europa, certainly one of Jupiter’s largest moons, is taken into account one of the crucial promising places within the solar system to look for extraterrestrial life.

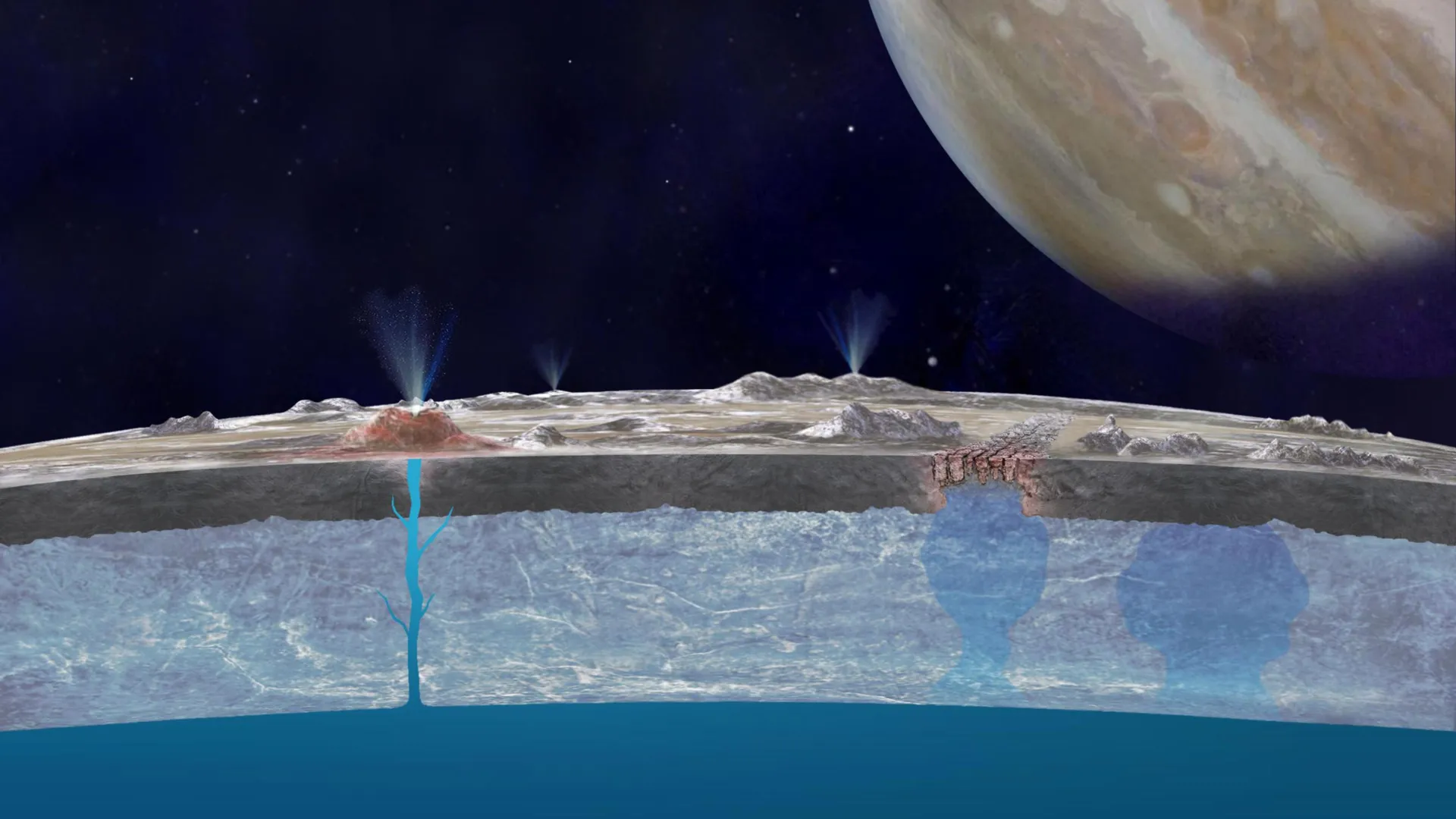

For years, scientists have struggled to clarify how life-supporting materials might move from Europa’s surface right down to its ocean, which is sealed beneath a thick layer of ice. Researchers used computer simulations inspired by a geological process on Earth called crustal delamination. Their models suggest that dense ice filled with nutrients can break away from surrounding ice and slowly sink through the shell until it reaches the ocean below.

“This can be a novel idea in planetary science, inspired by a well-understood idea in Earth science,” said Austin Green, lead writer and postdoctoral researcher at Virginia Tech. “Most excitingly, this recent idea addresses certainly one of the longstanding habitability problems on Europa and is an excellent sign for the prospects of extraterrestrial life in its ocean.”

Why Europa’s Ocean Poses a Habitability Puzzle

The research was published in The Planetary Science Journal and authored by Green, who accomplished much of the work during his doctoral studies at WSU, together with Catherine Cooper, an associate professor of geophysics within the School of Environment and associate dean within the College of Arts and Sciences.

Europa holds more liquid water than all of Earth’s oceans combined. Nevertheless, that vast ocean sits beneath an icy shell so thick it blocks sunlight entirely. Without sunlight, any life in Europa’s ocean would wish alternative sources of energy and nutrients, raising long-standing questions on whether the environment could actually support living organisms.

Adding to the complexity, Europa is always exposed to intense radiation from Jupiter. This radiation reacts with salts and other materials on the moon’s surface, producing compounds that might function nutrients for microbes. While scientists know these nutrients exist on the surface, it has remained unclear how they might move downward through the ice to succeed in the ocean. Although Europa’s surface is geologically lively attributable to Jupiter’s gravitational forces, most of that motion occurs sideways somewhat than downward, limiting direct exchange between the surface and the ocean.

Borrowing an Idea From Earth’s Geology

To tackle this problem, Green and Cooper turned to Earth for inspiration. They focused on crustal delamination, a process through which sections of Earth’s crust change into compressed, chemically altered, and dense enough to detach and sink into the mantle below.

The researchers believed the same process could occur on Europa. Certain areas of Europa’s ice shell contain high concentrations of salt, which increases the density of the ice. Previous research has also shown that impurities weaken the structure of ice crystals, making them less stable than pure ice. For delamination to occur, this weakened ice would wish to interrupt free and sink deeper into the ice shell.

How Dense Ice Could Feed Europa’s Ocean

The team proposed that heavy, salt-rich ice embedded inside purer ice could slowly descend through the shell, recycling surface material and delivering nutrients to the ocean. Their computer models showed that this sinking could occur across a wide selection of salt levels, so long as the surface ice experiences even modest weakening.

In line with the simulations, the method could occur relatively quickly on geological timescales and repeat over long periods. That makes it a potentially regular and reliable option to transport nutrients into Europa’s ocean, improving the possibilities that life could survive there.

Relevance to NASA’s Europa Clipper Mission

These findings align closely with the goals of NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, which launched in 2024. The spacecraft is designed to check Europa’s ice shell, subsurface ocean, and overall habitability using a set of scientific instruments.

The research was supported partly by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Grant NNX15AH91G and relied on computing resources from the Center for Institutional Research Computing at Washington State University.