For countless ages, a small chunk of ice and mud traveled alone through interstellar space, like a sealed bottle drifting across an unlimited cosmic sea.

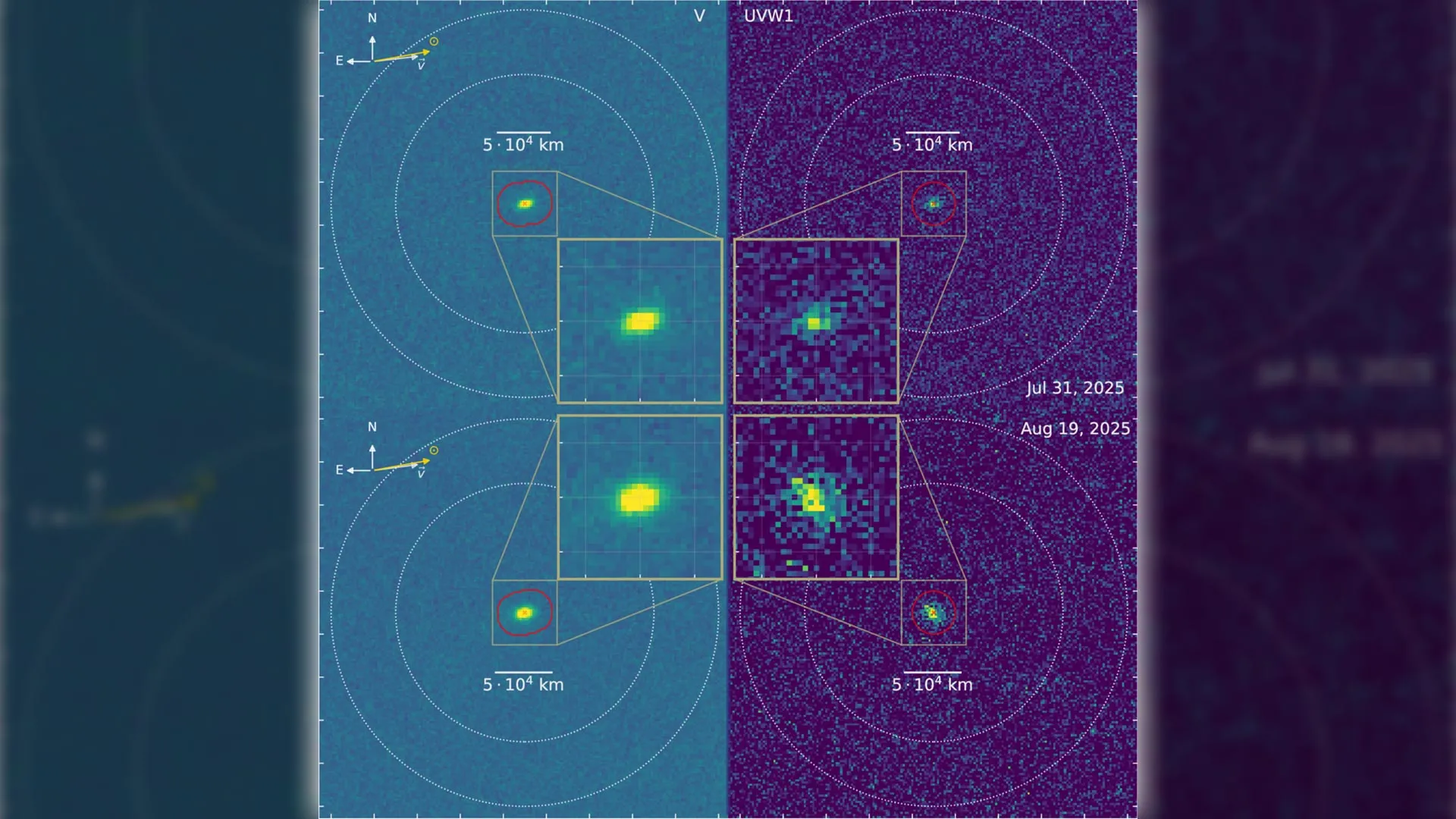

This summer, that traveler entered our solar system and received the name 3I/ATLAS, becoming only the third confirmed interstellar comet ever observed. When researchers at Auburn University aimed NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory at the item, they uncovered something extraordinary: the primary detection of hydroxyl (OH) gas coming from it, a transparent chemical sign of water. Swift was capable of detect a faint ultraviolet glow that ground based telescopes cannot see since it operates above Earth’s atmosphere, where this sort of light isn’t blocked before reaching the surface.

First Detection of Water on Interstellar Comet 3I/ATLAS

Identifying water through its ultraviolet byproduct, hydroxyl, marks a vital step in understanding how interstellar comets behave and alter over time. In comets that formed inside our own solar system, water serves as the first measure of activity. Scientists use it to find out how sunlight triggers the discharge of other gases and to match the combination of frozen materials inside a comet’s nucleus. Detecting the identical water signature in 3I/ATLAS means astronomers can now evaluate it using the identical standards applied to familiar solar system comets. That comparison opens the door to studying how planetary systems across the galaxy may differ or resemble our own.

Unexpected Water Activity Far From the Sun

What makes 3I/ATLAS especially intriguing is the gap at which this water activity was observed. Swift detected hydroxyl when the comet was nearly 3 times farther from the Sun than Earth is, well beyond the region where surface ice would normally turn directly into vapor. Even at that distance, the comet was losing water at a rate of about 40 kilograms per second, comparable to water blasting from a completely opened fire hose. Most comets native to our solar system remain relatively inactive that far out.

The strong ultraviolet signal suggests that additional processes could also be involved. One possibility is that sunlight is warming tiny icy particles which have broken away from the nucleus. As those grains heat up, they may release vapor and provide the encircling cloud of gas. Only a small variety of distant comets have shown this type of prolonged water source, and it points to layered ices that will preserve details about how and where the item originally formed.

Clues to Planet Formation Beyond Our Solar System

Each interstellar comet discovered thus far has revealed something different about chemistry in other planetary systems. Together, these visitors show that the ingredients that construct comets, especially volatile ices, can vary widely from one star system to a different. Those differences provide insight into how temperature, radiation, and chemical makeup shape the materials that eventually form planets and possibly create conditions suitable for all times.

How NASA’s Swift Observatory Made the Discovery

Detecting that faint ultraviolet signal was also a technical achievement. NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory carries a comparatively small 30 centimeter telescope, yet from its position in orbit it might probably observe ultraviolet wavelengths which might be mostly absorbed by Earth’s atmosphere. Without interference from air and sky brightness, Swift’s Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope can reach a sensitivity comparable to a 4 meter class ground telescope at those wavelengths. Its ability to reply quickly allowed the Auburn team to look at 3I/ATLAS inside weeks of its discovery, before it became too faint or moved too near the Sun for secure remark from space.

“After we detect water — and even its faint ultraviolet echo, OH — from an interstellar comet, we’re reading a note from one other planetary system,” said Dennis Bodewits, professor of physics at Auburn. “It tells us that the ingredients for all times’s chemistry should not unique to our own.”

“Every interstellar comet thus far has been a surprise,” added Zexi Xing, postdoctoral researcher and lead creator of the study. “‘Oumuamua was dry, Borisov was wealthy in carbon monoxide, and now ATLAS is giving up water at a distance where we didn’t expect it. Each is rewriting what we thought we knew about how planets and comets form around stars.”

3I/ATLAS has since dimmed and is currently out of view, however it is predicted to develop into observable again after mid November. That return will give scientists one other opportunity to observe how its activity changes because it moves closer to the Sun. The detection of hydroxyl, detailed in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, offers the primary solid proof that this interstellar comet is releasing water removed from the Sun. It also highlights how even a modest space based telescope, operating above Earth’s atmosphere, can capture faint ultraviolet signals that connect this rare visitor to the broader family of comets and to the distant planetary systems where such objects are born.