Gene editing is a numbers game. For any genetic tweaks to have notable impact, a sufficient variety of targeted cells must have the disease-causing gene deleted or replaced.

Despite a growing gene-editing arsenal, the tools share a typical shortcoming: They only work once in whatever cells they reach. Viruses, in contrast, readily self-replicate by hijacking their host’s cellular machinery after which, their numbers swelling, drift to contaminate more cells.

This strategy inspired a team on the University of California, Berkeley and collaborators to switch the gene editor, CRISPR-Cas9, to similarly replicate and spread to surrounding cells.

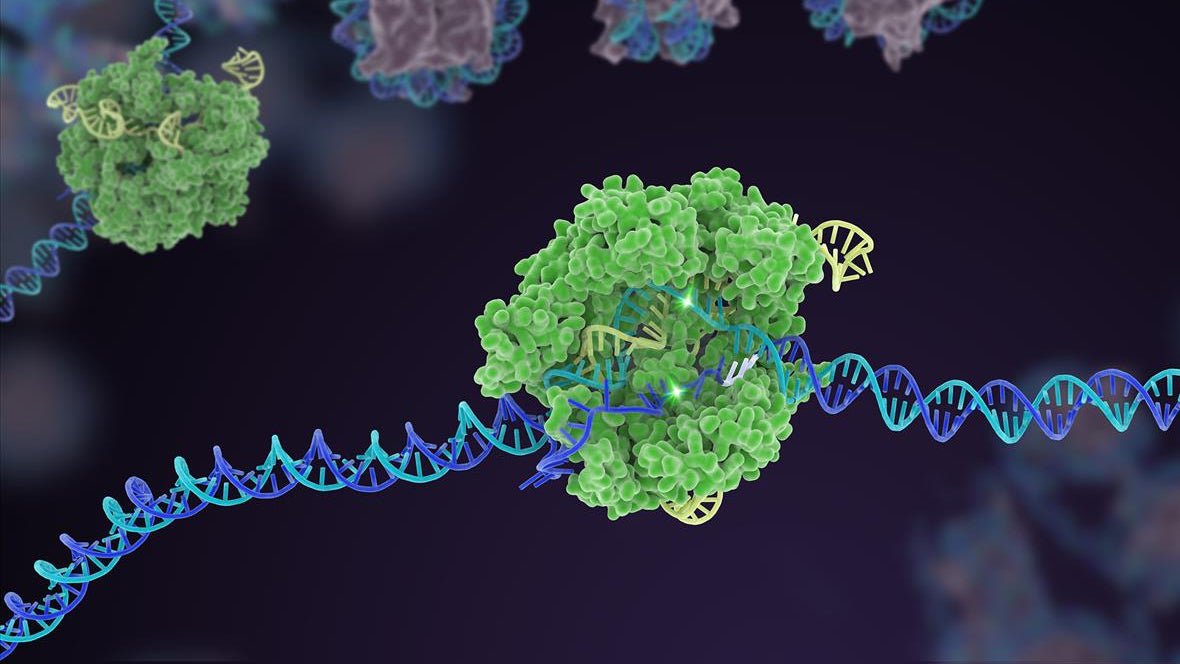

Led by gene-editing pioneer and Nobel Prize winner, Jennifer Doudna, the scientists added genetic instructions for cells to make a virus-like transporter that may encapsulate the CRISPR machinery. Once manufactured in treated cells, the CRISPR cargo ships to neighboring cells.

The upgraded editor was roughly 3 times more practical at gene editing lab-grown cells compared to straightforward CRISPR. It also lowered the quantity of a harmful protein in mice with a genetic metabolic disorder, while the unique version had little effect at the identical dose.

The technology is “a conceptual shift within the delivery of therapeutic cargo,” wrote the team in a bioRxiv preprint.

Recoding Genetics

CRISPR has completely transformed gene therapy. In only a couple of years, the technology exploded from a research curiosity right into a biotechnology toolbox that may tackle previously untreatable inherited diseases. Some CRISPR versions delete or inactivate pathogenic genes. Others swap out single mutated DNA letters to revive health.

The primary CRISPR therapies deal with blood disorders and require doctors to remove cells from the body for treatment. The therapies are tailored to every patient but are slow and expensive. To bring gene therapy to the masses, scientists are developing gene editors that edit DNA directly contained in the body with a single injection.

From reprogramming faulty blood cells and treating multiple blood disorders to lowering dangerous levels of cholesterol and tackling mitochondrial diseases, CRISPR has already proven it has the potential to unleash a brand new universe of gene therapies at breakneck speed.

Gene editors “promise to revolutionize medicine by overriding or correcting the underlying genetic basis of disease,” wrote the team. But all these tools are throttled by one basic requirement: Enough cells must be edited that they override their diseased counterparts.

What number of is dependent upon the genetic disorder. Treatments must correct around 20 percent of blood stem cells to maintain sickle cell disease at bay. For Duchenne muscular dystrophy, an inherited disease that weakens muscles, over 15 percent of targeted cells must be edited.

These numbers could appear low, but they’re still difficult for current CRISPR technologies.

“Once delivered to cells, editing machinery is confined to the cells it initially enters,” wrote the team. To compensate, scientists often increase the dosage, but this risks triggering immune attacks and off-target genetic edits.

Work Smarter, Not Harder

Although membrane-bound and seemingly isolated, cells are literally quite chatty.

Some cells package mRNA molecules into bubbles and eject them towards their neighbors, essentially sharing instructions for tips on how to make proteins. Other cells, including neurons, form extensive nanotube networks that shuttle components between cells, akin to energy-producing mitochondria.

Inspired by these mechanisms, scientists have transferred small proteins and RNA across cells. So, the team thought, why couldn’t an analogous mechanism spread CRISPR too?

The team adapted a carrier developed a couple of years back from virus proteins. The proteins routinely form a hole shell that buds off from cells, drifts across to neighboring cells, and fuses with them to release encapsulated cargo.

The system, called NANoparticle-Induced Transfer of Enzyme, or NANITE, combines genetic instructions for the carrier molecules and CRISPR machinery right into a single circular piece of DNA. This ensures the Cas9 enzyme is physically linked to the delivery proteins as each are being made inside a cell. It also means the ultimate delivery vehicle encapsulates guide RNA as well, the “bloodhound” that tethers Cas9 to its DNA goal.

Like a benevolent virus, NANITE initially “infects” a small variety of cells. Once inside, it instructs each cell to make the complete CRISPR tool, package it up, and send it along to other cells. Uninfected cells absorb the cargo and are dosed with the gene editor, allowing it to spread beyond treated cells.

In comparison with classic CRISPR-Cas9, NANITE was roughly 3 times more efficient at editing multiple kinds of cells grown in culture. Adding protein “hooks” helped NANITE locate and latch on to specific populations of cells with an identical “eye” protein, increasing editing specificity. NANITE punched far beyond its weight: Edited cells averaged nearly 300 percent of the initially treated number, suggesting the therapy had spread to untreated neighbors.

In one other test, the team tailored NANITE to slash a disease-causing protein called transthyretin within the livers of mice. Mutations to the protein eventually result in heart and nerve failure and might be deadly. The researchers injected NANITE directly into the rodents’ veins using a high-pressure system. This system reliably sends circular DNA to the liver, the goal organ for the disease, and shows promise in people.

Inside per week, NANITE had reduced transthyretin nearly 50 percent while editing only around 11 percent of liver cells. Such results would likely improve and stabilize the disease in accordance with previous clinical trials, although the team didn’t report symptoms. In contrast, classic CRISPR-Cas9 only edited 4 percent of cells and had minimal effect on transthyretin production.

The failure could possibly be since the gene editor was confined to a small group of cells, whereas NANITE spread to others, “enabling more efficient tissue-level editing,” wrote the team. Extensive liver and blood tests in mice treated with NANITE detected no toxic unwanted effects.

A 3-fold boost in editing is only the start. The team is working to extend NANITE efficacy and to potentially convert the system into mRNA, much like the technology underlying Covid-19 vaccines. In comparison with shuttling circular DNA into the body—a long-standing headache—there may be a far wider range of established delivery systems for mRNA.

Still, these early results suggest it’s possible to “amplify therapeutic effects by spreading cargo” beyond the initially edited cells. Avoiding the necessity for relatively large doses, NANITE could increase the security profile of gene-editing treatments and potentially expand the technology to tissues and organs which can be more difficult to genetically alter than the liver.

The technology changes the numbers game. Even when only a fraction of the NANITE therapy reaches its goal tissue, its ability to spread could still deliver enough impact to cure currently untouchable genetic diseases. “By lowering effective dose requirements, NANITE could make genome editing more practical and accessible for treating human disease,” wrote the team.